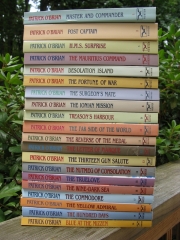

It was with some degree of sadness that I closed the cover of Patrick O’Brian’s “Blue at the Mizzen” last evening. The act marked the end of my second trip through the twenty-volume series since I first had “Master and Commander” recommended to me by my brother ten years ago or more. I enjoyed this journey every bit as much as, and perhaps more than, the first. But even as I savored those final pages melancholy crept in, hard on the heels of the almost certain knowledge that it would be my last visit to O’Brian’s world. I was saying good bye to Captain (nay, Admiral!) Aubrey and the Doctor, for good. I will reread a book more than once, even many times. I have read the four books in the main trunk of Tolkien’s work something like eight or nine times, at least. But I have to read them all, and in order, and well, there are twenty of them in O’Brian’s tale.

It takes a significant portion of a person’s life to read twenty novels once. It must be a truly rare writer who could motivate a second helping, and perhaps no writer living or dead could prompt a third. O’Brian was every bit that writer: fit to inhabit the same exalted perch and breathe the same rarified air as Conrad, London, Wells, Verne, and Forester. To be sure, O’Brian cannot claim their variety of subject matter and point of view, and there are some who might smirk at the literary pretensions of what we must all admit was a six-thousand page serial adventure novel, but I don’t believe many who have read the books would share that view. O’Brian was in many ways a one-hit wonder, but what a prodigious great hit it was. Page after lyrical, poetical page, the tales of Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin are an antiquarian feast for the literary senses.

And if it requires a rare writer to prepare such a feast, maybe it needs a rare reader to take a seat at the table once it is served. Great length is not the only characteristic of this tale that might deter the faint-hearted amateur. One of the great distinguishing features of O’Brian’s work is the language. Among the things novelists strive for are style, voice, and a sense of place. In the Aubrey-Maturin novels O’Brian emerged in the eye of the reading world as a master craftsman, whose every sentence, every perfectly placed paragraph, was so thoroughly steeped in the time, or his sense of it, that while reading them you found yourself immersed without ever feeling the water around your ankles. But this language can be daunting to those accustomed to the modern novel, that often flies by with the breathless pace of a movie. I have relatives who have tried to read O’Brian, but simply have not been able to make headway, even though they love a good sea story.

And it is as a sea story, one immensely long glorious sea story, that O’Brian’s work truly shines. He is neither as dark as Conrad, as gritty as London, nor as fanciful as Verne, and his vision of life at sea is somewhat too idealized to be read as history, but for an authentic image of an eighteenth-century full-rigged ship and its working he is not to be matched. For this he drew on comprehensive research, and personal experience. I am probably in a minority of O’Brian readers who have spent a significant amount of time in square-rigged wooden ships. I spent a large part of 1984 and 1985 sailing as crew aboard first a barkentine (square-rigged foremast, fore-and-aft-rigged main and mizzen) of 180′, and then a brigantine (same rig, one less mast) of 140′. Like the characters in “Master and Commander” and its sequels, I have been aloft in a blow, and know what it is like to lay out on a yard a hundred feet above deck, with one hand for the ship, and one hand for yourself. There is not one detail of O’Brian’s descriptions, from chainplates to futtock shrouds, from wearing to clubhauling, that did not ring true for me.

As authentic as they are, the novels are not one unbroken success from front to back. Some are better than others, and I think that on my second time through I read them with a somewhat more critical eye. Beginning with “The Yellow Admiral” I began to get a sense that perhaps O’Brian knew that things were getting a little repetitive, and even more to the point, he himself acknowledged, in one of the few forewords that he wrote, that he was “running out of history.” If he had known the story would be so popular, he said, then he might have begun in the 1780’s or even earlier. There was a great deal of smacking good Royal navy history that had passed beyond the tale’s reach when he decided to bring the Doctor and the Lieutenant together in Minorca in the year 1800. I doubt, though, that the tale would have been better for an earlier start.

Nor is it improved by a later end. There is a 21st “book” in the series, but I won’t read it. Published after the author died in Dublin in 2000, it consists of a couple of typeset chapters and some handwritten treatments and notes. If they are an accurate guide to the plot, then it seems that O’Brian, at least, was not yet tired of his characters. But for me the perfect ending is “Blue at the Mizzen.” I am content to see Jack with the promise of his pennant, and Stephen with the hope of Christine to salve his wounds, and all of them frozen forever in memory, riding to anchor in the bay of Valparaiso and looking after home and hearth at Woolcombe. The twenty books O’Brian actually completed give us the grand arc of the character’s lives from start to satisfying finish, from jobless Lieutenant to respected Admiral, from penniless surgeon to wealthy naturalist, and there is really nothing more that a reader can ask from an author. By any measurement, Patrick O’Brian gave this reader more pleasure to the page than he had any right to expect.